PIME Martyrs

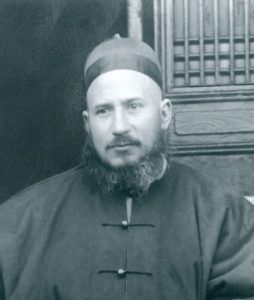

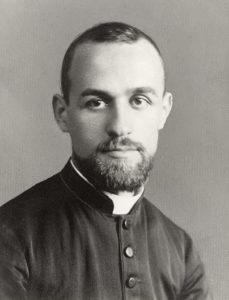

St. Alberic Crescitelli was ordained in 1887 and assigned to serve in China. After briefly studying the Chinese language, he was sent to the Sijiaying district where a thousand Christians lived among seven villages.

St. Alberic Crescitelli was ordained in 1887 and assigned to serve in China. After briefly studying the Chinese language, he was sent to the Sijiaying district where a thousand Christians lived among seven villages.

Transferred to the even more remote region of Ninqiang in 1900, Fr. Alberico served with peace and confidence, even though his efforts were met with indifference and even hostility. During this period of the Boxer rebellion, an imperial decree was issued from Peking, sentencing to death all Christians who refused to renounce their religion and ordering the deportation of all foreign missionaries.

Fr. Alberico did not wish to leave, but was persuaded to seek protection from the local mandarin. A gang captured him; he was brutally tortured for more than a day, then decapitated and dismembered, his body cast into the river.

He was proclaimed 'Blessed' by Pope Pius XII on February 18, 1951 and 'Saint' by Pope John Paul II on October 1, 2000. The missionaries celebrate his feast day on February 18, and with the Chinese Martyrs on July 9.

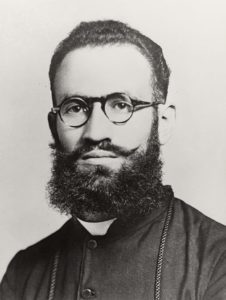

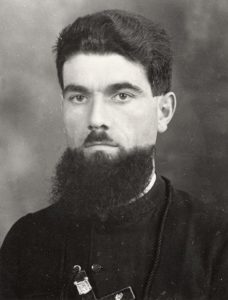

Blessed John Mazzucconi, PIME’s first martyr, was sent to Oceania with four other priests in 1852. They replaced the Marists, anxious to serve in this difficult and dangerous mission. By doing so they lived out one of the core tenets of the newly formed missionary institute – to serve “among the most neglected and primitive of peoples.”

Blessed John Mazzucconi, PIME’s first martyr, was sent to Oceania with four other priests in 1852. They replaced the Marists, anxious to serve in this difficult and dangerous mission. By doing so they lived out one of the core tenets of the newly formed missionary institute – to serve “among the most neglected and primitive of peoples.”

Almost immediately upon arriving, Fr. John contracted malaria, and suffered greatly from almost daily fevers. Conditions were extremely harsh. However, Fr. John and his companions did not complain, despite the fact that in addition to the physical hardships they had to endure, the people of Woodlark were not receptive to them, and were in fact hostile.

Weakened almost to the point of death, he was sent to Australia for a period of convalescence. He eagerly returned to the mission, not knowing his companions were either dead or had already abandoned the mission. He was martyred with all the crew of "La Gazelle," presumably on September 25, 1855, in Woodlark Bay. He was proclaimed 'Blessed' by Pope John Paul II on February 19, 1984 and his feast day is September 25.

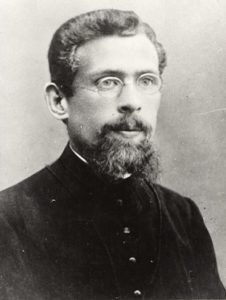

Fr. Mencattini arrived at the PIME seminary in Agazzi, Italy when he was only 17. Passionate about become a missionary priest, he committed himself to his studies and was ordained on September 22, 1934. Immediately, along with several classmates, he was sent to China.

Fr. Mencattini arrived at the PIME seminary in Agazzi, Italy when he was only 17. Passionate about become a missionary priest, he committed himself to his studies and was ordained on September 22, 1934. Immediately, along with several classmates, he was sent to China.

His mission assignment was a difficult one. Physical sufferings accompanied the emotional ones; the Chinese people, who called them “European dogs”, met them with disdain. The political situation soon became confusing and dangerous, with Chinese troops, the Japanese, brigands, and communists competing for control.

Fr. Mencattini struggled to the serve the Christian people of the Huaxian district, building simple chapels and training catechists. He also struggled to remain neutral as the control of the region continually changed hands.

On July 12, 1941, he fell victim to an assault by a band of Chinese soldiers. He was shot and then stabbed with a bayonet. In the same incident Frs. Angelo Bagnoli and Leo Cavallini were wounded.

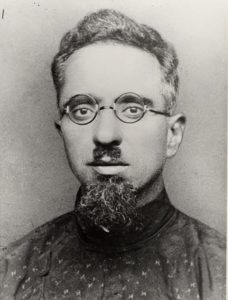

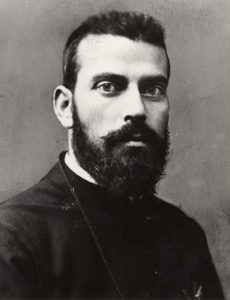

Bishop Barosi entered the seminary in 1913, convinced he would become a diocesan priest. After hearing a talk given by a missionary to India, he changed his mind. God was calling him to the life of a missionary. He was ordained on October 5, 1919; the next day he left for China.

Bishop Barosi entered the seminary in 1913, convinced he would become a diocesan priest. After hearing a talk given by a missionary to India, he changed his mind. God was calling him to the life of a missionary. He was ordained on October 5, 1919; the next day he left for China.

He struggled with language and the new environment, and the harsh reality of Chinese communism. He developed skills of organization and diplomacy which, coupled with his great faith, contributed to his eventual appointment as Apostolic Vicar of Kaifeng, in the province of Henan.

His first duty in that position was to visit all of the districts in his jurisdiction; in late fall of 1941 only one remained, in Dingcunji. With good reason, that region was known as a “no man’s land;” there was no central authority and a wide variety of occupying forces vied for control. It is during his visit there that he is martyred along with Frs. Zanardi, Zanella and Lazzaroni. He was tied up, choked to death and thrown into the well near Luyi, by Chinese soldiers, on November 19, 1941.

Gerolamo Lazzaroni came from a poor farming family in the tiny village of Colere, Italy. He dreamed of entering the seminary from a young age, but was told there was no way the family could afford such an education. Eventually he was allowed to leave for Bergamo – with only a third grade education.

Gerolamo Lazzaroni came from a poor farming family in the tiny village of Colere, Italy. He dreamed of entering the seminary from a young age, but was told there was no way the family could afford such an education. Eventually he was allowed to leave for Bergamo – with only a third grade education.

He found seminary life difficult at first, but eventually became an excellent student. During his high school years he transferred to the PIME seminary in Genoa. By the age of 24 he was ordained and told of his destination as a missionary: China.

More than anything he desired to be a preacher, and he shared the Gospel with all who would listen. He also had a special gift for working with children, and he enjoyed teaching them their catechism. He also assisted Fr. Bruno Zanella, who had been named pastor of the parish in Kaifeng.

Along with Fr. Bruno he was martyred on November 19, 1941. With the Monsignor and Frs. Zanella and Zanardi, he was tied up, choked to death and thrown into the well near Luyi, by Chinese soldiers.

In June of 1927 Fr. Zanardi was ordained. A few weeks later he set out on the three-month journey by sea to China.

In June of 1927 Fr. Zanardi was ordained. A few weeks later he set out on the three-month journey by sea to China.

His first duty in China was to learn the language. In only four months he was able to hear confessions in Chinese, and he gained acceptance and respect in the Christian community. But that community was small and spread over a vast district, in an area infested with bandits.

More than anything he desired to be a preacher, and he shared the Gospel with all who would listen. He also had a special gift for working with children, and he enjoyed teaching them their catechism. He also assisted Fr. Bruno Zanella, who had been named pastor of the parish in Kaifeng.

He was eventually named vicar of the district. In that capacity he could see even more clearly the many challenges of the people; their land was war-torn and impoverished, they were poor and without hope.

Fr. Zanardi agreed to accompany Bishop Barosi when he announced his plan to visit Dingcunji in the fall of 1941. It would be a welcome reunion with his old friend and classmate.

During this visit he was martyred along with the Bishop and Frs. Zanella and Lazzaroni. He was tied up, choked to death and thrown into the well near Luyi, by Chinese soldiers, on November 19, 1941.

After years of difficult study – he was not naturally endowed with great academic ability – Bruno Zanella was ordained a priest in September of 1935. He set out for China with two companions soon after. After studying the language for almost a year, he was first sent to work in the city rather than in a remote mission district. He was given several temporary assignments before being finally sent to Dingcunji, the farthest and most difficult district.

Fr. Zanella spent much time educating the people of his district in the Catholic faith. In fact, he had just prepared a group to be confirmed in time for a visit from Bishop Barosi, who was coming to check on the progress of Fr. Zanella among the people.

More than anything he desired to be a preacher, and he shared the Gospel with all who would listen. He also had a special gift for working with children, and he enjoyed teaching them their catechism. He also assisted Fr. Bruno Zanella, who had been named pastor of the parish in Kaifeng.

It is during this visit that Fr. Zanella was martyred along with the Bishop and Frs. Zanardi and Lazzaroni. He was forced to swallow boiling water and oil and then thrown into the well near Luyi, by Chinese soldiers, on November 19, 1941.

Fr. Carlo arrived in Kaifeng, China in 1924. He was first assigned to teach in the seminary, and then sent to Yuanzhai, a dangerous region known to be rife with armed bandits. Knowing he had a great fear of the brigands, his bishop sent him to Kaifeng and appointed him assistant pastor of the Cathedral and chaplain of the orphanage.

Fr. Carlo arrived in Kaifeng, China in 1924. He was first assigned to teach in the seminary, and then sent to Yuanzhai, a dangerous region known to be rife with armed bandits. Knowing he had a great fear of the brigands, his bishop sent him to Kaifeng and appointed him assistant pastor of the Cathedral and chaplain of the orphanage.

During his 18 years in China, Fr. Carlo thought often of martyrdom, considering himself the most unlikely martyr. He was so timid that he thought he would never have the courage to die for his faith. But his faith was strong, and he prayed for the graces he would need.

Eventually the turmoil came also to Kaifeng. Fr. Carlo, along with a catechist and a young boy, the son of the local mandarin, he was kidnapped and held for 20 days. On February 2, 1942, he was told he would be released. Instead, he was dragged from his hut and bound hand and foot. Then he was buried alive in a pit, martyred for his commitment to the Chinese people and his Catholic faith.

In the 1940’s, the north coast of Hong Kong was beset with intense political conflicts. Communications between Haifeng and Hong Hong Kong passed through the vast region of Cairn. There Fr. Emilio Teruzzi was assigned to serve in 1914, when he began administration of the district.

In the 1940’s, the north coast of Hong Kong was beset with intense political conflicts. Communications between Haifeng and Hong Hong Kong passed through the vast region of Cairn. There Fr. Emilio Teruzzi was assigned to serve in 1914, when he began administration of the district.

In 1941 the Japanese invaded Hong Kong; in the year that followed misery, famine and abuses continued. Brigands, communists and bands of guerrillas took advantage of the confusion to raid the villages.

Fr. Terruzzi was warned not to go visit the small villages, because the guerilla bands considered him a traitor to China. Dedicated to his people, he continued to set out to visit the 15 chapels he cared for.

On a late fall day in 1942, Fr. Emilio was captured as he was preparing to celebrate the Eucharist in the home of some Christians. He was thrown into the sea near the coast of Sam Chung, Sai Kung District, New Territories, Hong Kong, most probably at the hands of Communist guerrillas, on November 26, 1942.

Mario Vergara grew up with his four brothers and four sisters in the industrial town of Frattamaggiore, Italy. Adventurous and fun-loving, young Mario entered the seminary immediately after elementary school. In October of 1929, he transferred to the PIME Seminary of Monza.

Mario Vergara grew up with his four brothers and four sisters in the industrial town of Frattamaggiore, Italy. Adventurous and fun-loving, young Mario entered the seminary immediately after elementary school. In October of 1929, he transferred to the PIME Seminary of Monza.

Upon his ordination in 1934, he was immediately sent to his mission assignment in Burma. He began his service in the district of Citacio, where there were 29 Catholic villages to attend to. He took on dozens of roles: priest, educator, doctor, administrator and often even judge.

When Italy declared war on England in June of 1940, the Italian missionaries were considered “fascists” and automatically became enemies of the British. Fr. Mario was detained for four years. In 1946 he set out for a new assignment in two Catholic villages. There he started with nothing and eventually built a community. By 1950 the area gained independence from Britain, but was affected by a civil war.

Rebels saw the priests as a threat. Along with Fr. Pietro Galastri, Fr. Mario and his catechist companion were shot and and thrown into the Salween River on May 24, 1950. Fr. Mario was declared blessed by Pope Francis in 2014.

From the age of 13, Pietro Galastri knew he wanted to become a priest. By 1937 he was studying in the PIME seminary in Monza and World War II was beginning. It was so dangerous there that he had to transfer to Brianza, and his ordination was put off until 1943. He was ready to be sent to the missions right away, but since the War was going on, he had to wait until 1948. By then he was 30 years old and very eager to begin his mission in Burma.

From the age of 13, Pietro Galastri knew he wanted to become a priest. By 1937 he was studying in the PIME seminary in Monza and World War II was beginning. It was so dangerous there that he had to transfer to Brianza, and his ordination was put off until 1943. He was ready to be sent to the missions right away, but since the War was going on, he had to wait until 1948. By then he was 30 years old and very eager to begin his mission in Burma.

Recognizing his tireless, hard working nature, the bishop sent him to the most difficult and dangerous post. There he undertook enormous work, including the building of a church, school, an orphanage and a dispensary. When the region was taken over by the rebels, his community became even more cut off from outside support.

The guerilla warfare intensified as the 1940’s came to a close. He was martyred, along with Blessed Mario Vergara, on May 24, 1950. Like Blessed Vergara he was shot to death and then thrown into the Salween River.

Alfredo Cremonesi was such a sickly young man that it seemed unlikely that he would live, let alone become a missionary. Afflicted with disease, he spent much of his school years in bed. When it seemed certain he would die, he was miraculously cured. He attributed this to the intercession of St. Therese of the Child Jesus, who is also patroness of the missions, perhaps that he why he transferred from the diocesan to the missionary seminary upon his recovery.

Alfredo Cremonesi was such a sickly young man that it seemed unlikely that he would live, let alone become a missionary. Afflicted with disease, he spent much of his school years in bed. When it seemed certain he would die, he was miraculously cured. He attributed this to the intercession of St. Therese of the Child Jesus, who is also patroness of the missions, perhaps that he why he transferred from the diocesan to the missionary seminary upon his recovery.

Impetuous and lively, he was also a gifted writer. In October of 1924, he was ordained. Exactly one year later he was sent to Burma.

There he suffered years of loneliness, poverty, and the results of political turmoil. In an isolated mountain village he worked among the Karen people, travelling many miles between communities. When Burma achieved independence in 1948, it was hoped peace would come. Instead, the central government faced great obstacles as the Karen tribes rebelled, engaging in guerilla warfare.

Fr. Alfredo became a martyr; shot by government troops, under the accusation of helping the Karen people, in Donoku, Myanmar, on February 7, 1953.

Pietro Manghisi was not always sure of God’s plan for him. Affected deeply by the comments of PIME Missionary Fr. Paolo Manna, who encouraged him to “make an offering of himself,” Pietro decided to give his life to the missionary priesthood. After studying in Milan, he was ordained on June 6, 1925. A few months later, along with 14 other missionaries, he sailed for Burma.

Pietro Manghisi was not always sure of God’s plan for him. Affected deeply by the comments of PIME Missionary Fr. Paolo Manna, who encouraged him to “make an offering of himself,” Pietro decided to give his life to the missionary priesthood. After studying in Milan, he was ordained on June 6, 1925. A few months later, along with 14 other missionaries, he sailed for Burma.

When World War II began, all Italian civilians were interned in concentration camps in India. Any Italian missionary in Burma for less than ten years was forced to leave his mission. Fr. Pietro, who was then a “veteran,” was allowed to remain in Lashio, but he had to remain inactive.

When the British retreated and the Japanese took charge, he was suspected of being a spy. He was sent back to Italy for a time, and then was allowed to return to Burma in 1950. He returned, now to a region ruled by Chinese nationalist troops. He was ambushed and shot to death by Chinese guerrillas, while in a jeep, approaching the Chinese border north of Lashio, Myanmar, on February 15, 1953.

Always feeling a strong bond between himself and his brother, Antonio, Fr. Eliodoro knew at 14 years old that he wanted to follow in Antonio’s footsteps on the day that he was given his Mission Cross and left for his distant mission in Burma. Throughout his time in the seminary, Eliodoro kept a letter from his brother in Mong Yong, within the letter was a brother’s plea: “Dear Brother, I live here with no house…I’m happy without friends, without teachers, I have days without hassles…and I will die without remorse…When will you come to keep me company?”

Always feeling a strong bond between himself and his brother, Antonio, Fr. Eliodoro knew at 14 years old that he wanted to follow in Antonio’s footsteps on the day that he was given his Mission Cross and left for his distant mission in Burma. Throughout his time in the seminary, Eliodoro kept a letter from his brother in Mong Yong, within the letter was a brother’s plea: “Dear Brother, I live here with no house…I’m happy without friends, without teachers, I have days without hassles…and I will die without remorse…When will you come to keep me company?”

Fr. Eliodoro’s brother Antonio died of Malaria three years before he himself set out for Burma. Fr. Eliodoro vowed: “I was hoping to help him, but God willing, I will replace him.” Setting out for Burma in 1934, Fr. Eliodoro finally made it to Mong Yang in 1936 after studying the Shan language. When WW II reached the area, the missionaries were sent to camps in India. In 1944 he is released but is unable to return to his mission until 1946.

Before his return he hears that his former mission has been burnt to the ground, and that he must start all over. Throughout reconstruction Fr. Eliodoro spends his compiling the first ever catechism written totally in the Khun language. He reached the bishop’s residence in Kengtung to get final approval of his catechism in September of 1955. Fr. Eliodoro set out in December to be back to his mission in time for Christmas. On his way back he is stopped by Chinese guerrillas raiding in the area, before he can react he is tied up and dragged into the forest. Burmese soldiers found him days later in the river, riddled with bullets. He is buried next to his brother, a testimony to faith among the remote villages of Burma.

After nine months of civil war, Bangladesh finally became a country on December 16, 1971. It was there that Fr. Angelo Maggioni served from 1948, when it was known as East Pakistan.

Ordained a priest for PIME at the age of 22, Fr. Angelo could not go to the missions immediately, as it was during World War II. So when he finally set out, he was eager to bring hope to the missionaries there, who had been isolated for years. At his first mission in Ruhea he discovered the misery of the people. They are malnourished and are constant victims of either extreme heat or flooding inherent in the region.

Fr. Angelo was named pastor in Andharkota, where he oversaw forty villages spread out in the territory of his parish. The mission became a center of food collection and distribution, especially for the many refugees who came from India. He was also, therefore, a target for the armed brigands who roamed the countryside.

He was killed by a band of these robbers in his mission residence on August 14, 1972.

Fr. Valeriano Fraccaro served as a missionary in main land China and Hong Kong for 37 years. He arrived in Hanzhong in 1937 at the age of 24 with literally nothing. He brought with him only his ever-present smile and sense of humor, coupled with a strong faith.

Fr. Valeriano Fraccaro served as a missionary in main land China and Hong Kong for 37 years. He arrived in Hanzhong in 1937 at the age of 24 with literally nothing. He brought with him only his ever-present smile and sense of humor, coupled with a strong faith.

He spent his first 14 years as a missionary in China, until he was expelled and labeled “an enemy of the people.” He managed to remain in Hong Kong, hoping to someday return to the mainland. Instead he would spend the remainder of his life serving the people of the border districts.

With a special love for children and the aged, he was well loved throughout the region. Fondly known as “Pope John” for his resemblance to the pontiff and “The Baker Priest” for his penchant for baking bread, he searched out the poorest of the poor.

His death on September 28, 1974 remains a mystery. The city he occupied was poor and affected by violence, but Fr. Valeriano threatened no one. Nevertheless, he was killed in his home in Sai Kung, New Territories, Hong Kong, attacked by an unknown assailant.

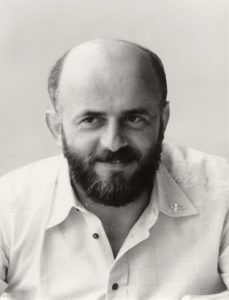

Fr. Tuillio Favali came to the PIME seminary after many years of discernment. After studying in a minor seminary from the age of 11, he spent time in the military, as a factory worker, in a dairy, and as a welder. Eventually dedicating himself more fully to spiritual development, he came into contact with PIME, eventually discerning he was called to a missionary life.

Fr. Tuillio Favali came to the PIME seminary after many years of discernment. After studying in a minor seminary from the age of 11, he spent time in the military, as a factory worker, in a dairy, and as a welder. Eventually dedicating himself more fully to spiritual development, he came into contact with PIME, eventually discerning he was called to a missionary life.

Open his ordination in 1981, he was sent to the new mission in Papua New Guinea. After spending time in the U.S., he was told he would be sent to a new mission assignment. He asked for any region other than America; he was intimidated by the size of the country and the people. He longed for a simpler environment.

He was sent to the Philippines where he would work in the poorest and most isolated area. Tululan was known as “the capital of terror” due to land wars and the presence of communist guerrillas. There were conflicts between Muslims and Christians, and the socio-political situation was difficult.

Fr. Tullio was gunned down by paramilitary troops at Tulunan, Kidapawan Diocese, Philippines, on April 11, 1985.

Ordained on July 15, 1971, Fr. Salvatore began his priestly life working among young people in Italy. He was naturally gifted at his assignment – forming a vocational community – but he longed to serve in the missions.

Ordained on July 15, 1971, Fr. Salvatore began his priestly life working among young people in Italy. He was naturally gifted at his assignment – forming a vocational community – but he longed to serve in the missions.

He received his mission assignment along with his two friends, Fr. Antimo Villano and Fr. Sebastiano D’Ambra. The three were sent to the Philippines. Siocon was desolate and remote, and held under a military regime and martial law. Muslim guerillas worked for independence from the central government of Manila. There was much violence and unrest, but Fr. Salvatore worked for dialogue and peace.

He worked with his companions in the Silsilah movement, promoting Christian-Muslim dialogue. (The organization received the National Peace Award in the Philippines in 1990.)

Fr. Salvatore was shot dead while driving back home after the first day of a Silsilah course on May 20, 1992. Some suspected Muslim extremists or the military killed him. Others believe he was killed by some person or group committed to stopping the dialogue between Christians and Muslims. The Silsilah movement remains active in Mindanao.

Fr. Fausto Tentorio, PIME was born on January 7, 1952 in Santa Maria di Rovagnate and raised in Santa Maria Hoe', in the Northern Italian town of Lecco. He was ordained in 1977 and left for the Philippines the following year; he would ultimately spend 30 years serving in the Philippines. Before the mission in Arakan he worked in a mission in Columbio, Sultan Kudarat, which was inhabited by Christians, Muslims and B'lang Indians.

Fr. Fausto Tentorio, PIME was born on January 7, 1952 in Santa Maria di Rovagnate and raised in Santa Maria Hoe', in the Northern Italian town of Lecco. He was ordained in 1977 and left for the Philippines the following year; he would ultimately spend 30 years serving in the Philippines. Before the mission in Arakan he worked in a mission in Columbio, Sultan Kudarat, which was inhabited by Christians, Muslims and B'lang Indians.

As a rural missionary and as an anti-mining advocate, he helped and worked with the indigenous peoples in opposing the operation of large-scale plantations and mining, which would harm them. As a human rights advocate, he joined in calling for justice for slain human rights workers and farmers in Central Mindanao.

A lone gunman shot Fr. Fausto, fondly called “Fr. Pops” by those who knew him, in broad daylight at the garage of the Our Mother of Perpetual Help Parish Church Convent, Arakan Valley, North Cotabato on October 17, 2011.